Writing is now my sole source of income. The Berlin Files will remain free for a short period of time - if you enjoy reading it, please do consider pledging your support!

As is well known, Germany serves beer in half litres and litres, which means I was pleasantly buzzed by the time my partner and I got to Mauerpark. The square was gradually filling up with protesters dressed in black, and the surrounding streets were packed with police vans and armed officers. It was 8pm on a balmy evening. The final day of April.

We were there because it was Walpurgisnacht, also known as Night of the Witches, Walpurgis Night or Saint Walpurga’s Eve. Walpurgis, as I’ll henceforth be calling it, is a Christian celebration that takes place every year on April 30th, going into the early hours of May 1st (Labour Day). Originally, this celebration was meant to commemorate Saint Walpurga, an 8th century missionary girlie from the Frankish empire (basically, almost all of Western Europe except, maybe, Spain? Or whatever existed before Spain) who travelled to Germany to evangelise all the pagans and convert them to Christianity. She later became a nun and then an Abbess, and was celebrated for battling rabies, diseases and…witchcraft! Stunning! In her honour, and also to ward off all the evil black magic, people began celebrating Walpurgis Night on April 30th because that was when all witches were allegedly partying up with the Devil on Brocken mountain.

Over time, Wulpurgis has become less saintly and more of a fun night out - people light bonfires, set off fireworks, play music, dress up as witches and also apparently prank each other. And becuase it’s Berlin, glorious, left-wing Berlin, the night has been embraced by the left as a night of protest (and occasional riots). So it makes sense then, that a feminist protest had been organised for that evening.

From witchcraft to anti-capitalism

There’s history between feminism, anti-capitalism and witchcraft, which at times feels intuitive. Women - in particular older women, single women, lower class, Disabled women and women of colour - were murdered in horrific numbers for the impossible to define crime of witchcraft. Anyone could be accused, and ‘evidence’ was either irrelevant or made up. Women were tortured and killed in horrific ways across Europe - in the name of religion, sure, but mostly as a pretext to violently enforce rigid social norms, control marginalised communities and settle petty grudges. Witches continues to spark fear and fascination, but they have also become a symbol of women’s resistance and liberation - as well as a political framework.

Any politics student who has read Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch will know that Federici directly connects the witch hunts of the 15th - 18th century to the world’s transition to capitalism, a socio-economic system that is entirely dependent on the subjugation of women (and colonialism). For Federici, the witch represents “the embodiment of a world of female subjects that capitalism had to destroy: the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, the obeha woman who poisoned the master’s food and inspired the slaves to revolt.”

I recommend reading the book (and this one) if you’re interested, because Federici charts a fascinating journey of how women were gradually pushed out of the workforce and into the home in order to propagate a new world order - a term known as ‘housewifisation’, coined by German Marxist ecofeminist Maria Mies and expanded on by Federici. It’s an academic text, so it is dense, but it’s brilliant.

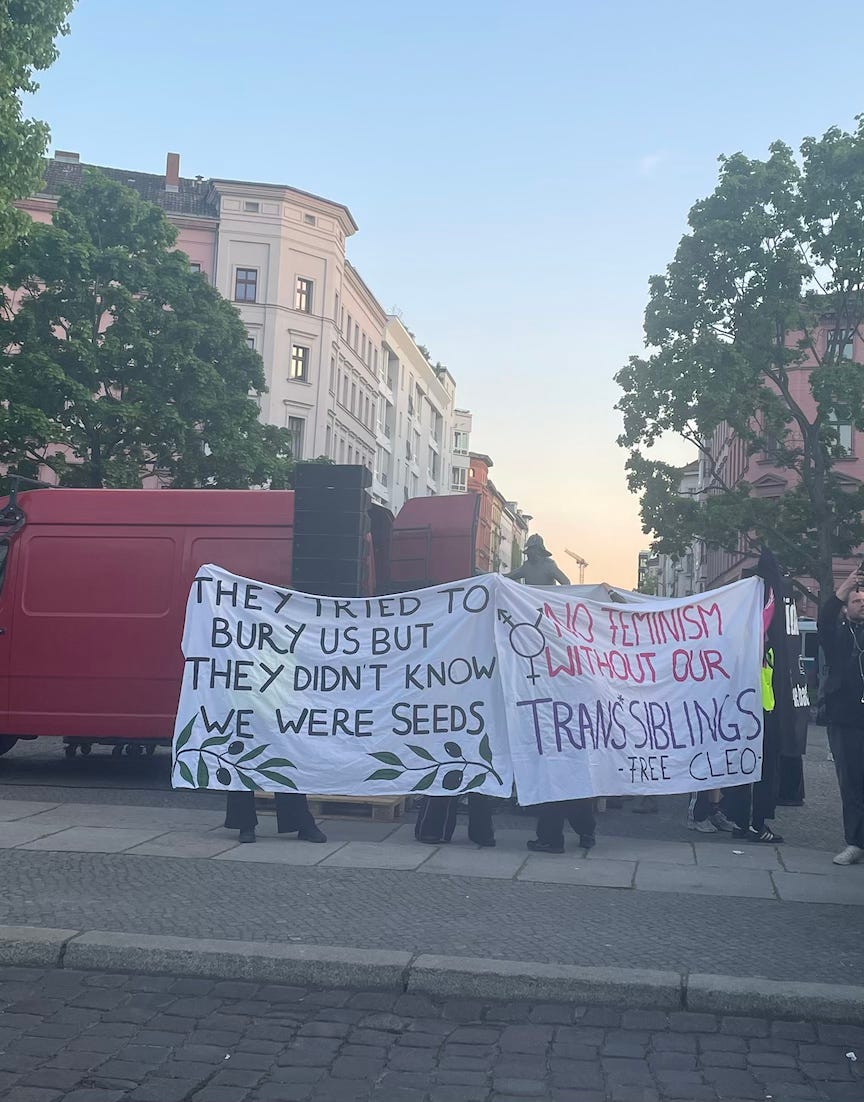

The point is, a night about witches is almost certainly going to become a centre of radical feminist protest, because history and context demands it. Especially in a place as politically literate as Berlin. My partner (J) found out about it through a work colleague, and we were both keen to attend. The meeting point was a large, grassy square on Eberswalder Straße, surrounded by restaurants, bars and residential buildings. When J and I got there, there was a small crowd drifting by the speakers as the organisers stood huddled together, their faces obscured by banners. It took a long time to get going. We went off to get ice cream, and by the time we got back the rally still had not started but the crowd had swelled. As had the police presence.

No such thing as a German community liaison officer

I wonder about how normalised police presence is in other countries. In the UK, its community liaison officers (annoying, not to be trusted, but less threatening) that tend to staff marches and protests. The real police only show up for the properly big ones that involve tens of thousands. And police in the UK are rarely armed, so it was jarring to see so many vans parked on adjacent streets, full of heavily armed officers. There were about fifty vans in total, a few hundred police officers positioned at every corner of the square. Over the course of the night, as the march moved through the city, we saw more and more waiting at certain checkpoints. It was bizarre and intimidating, which is obviously the point. Not that many people there seemed bothered. Most seemed to be seasoned demonstrators, who knew exactly what to chant and showed up in all black, their faces covered, keffiyehs tied around their shoulders and waists. The march was obviously intersectional, and the first hour and a half consisted of speeches from various political organisations in a mixture of German, English and Spanish. The underlying message was resolute: global solidarity or nothing. Israel’s genocide taking place in Palestine was at the core of every speech. Speakers talked about Congo and Sudan; the soaring rates of gender based violence in South America; abortion rights and the urgent need for trans solidarity - pointing to the recent decision of the UK Supreme Court to rule that the legal definition of a woman is based on biological sex. The crowd roared and clapped and sat on the grass sipping from beer bottles as it got dark. The police silently lined up outside the square, listening as the organisers lambasted their insanely heavy-handed presence. It was a both sobering stocktake of how fucked the world feels right now, and exhilarating reminder of how powerful it can feel when people show up. Demonstrations tend to have that effect, I think.

Throughout the speeches, the crowd was informed that the march was space for ‘FLINTA identified people’, FLINTA* being a German acronym meaning female, lesbian, intersex, non-binary, trans and agender. The asterisk represents all-gender or non-gender. The term is apparently a bit controversial as some have argued that it excludes those who may be read as cis-males - a tension the organisers were clearly very aware of, as they repeated over and over that no one’s gender should be presumed or polices. But at the same time, there was a large and visible presence of cis men - allies - who stood towards the back of the rally, even though no one was really sure if they were meant to be there or not. It threw me right back to my days working at the Women’s Equality Party, and the various challenges of trying to make a space that is inclusive, effective and safe. But, from my perspective at least, the crowd was great vibes. By 10pm, we were marching through the streets of Berlin. People leaned over their balconies and out their windows, phones held aloft as the police silently patrolled the edges.

Siamo tutti antifascisti

The Germans, as it turns out, are much better at protesting than the Brits. First of all, colourful smoke bombs. People were dropping them all over the place, then melting away into the crowd. Against the street lights, the smoke was atmospheric, the mood heightened. But the real winner was the chants. I’ve been to many protests, demos, rallies and marches in England - if the chants aren’t an organised and constant presence, people lose direction. Chants are vital, they keep the crowd focused and energised, they contain critical messaging, they draw others in. They’re what people remember, and it felt to me like everyone who had shown up really understood that. J, who has attended lots of protests in Germany, said that this was pretty standard - but to me it stood out right away.

My favourite by far was (randomly) an Italian chant that was paired with synchronised clapping. Siamo tutti antifascisti (we are all anti-fascist) comes from the Italian left and according to reddit, seems to be the default chant in Germany and other European countries. It was my first time hearing it, but I can see why it caught on - the phrase is melodic and deeply satisfying to say. When done right, you’re surrounded by hundreds of people clapping rhythmically after each sentence, and it looks and sounds amazing. I wish I’d managed to get video footage of the clapping (I was too busy clapping). You raise your hands above your head to clap, then hold them in air in a ‘don’t shoot’ motion which, when seen in the thousands, is pretty symbolically powerful.

I think it’s rare that marches manage to strike the balance between anger, grief, politics, solidarity, community, movement and joy. But when they do it right, you come away feeling really good - and I think that is important for sustaining yourself and the movement. It was moving to be a part of.

By midnight, the march had snaked towards our neighbourhood in east Berlin and we peeled off to make our way home. There was a party at the end of the march, but it was over an hour away, and we had to tap out. When we’d set off, J and I had been at the back of the crowd, but by the time we left we were squarely in the middle. We watched for almost ten minutes as rows and rows of people streamed past us, arms in the air, voices rising and falling. Following them, as ever, were about a hundred the blank-faced, uniformed police. I might get used to it eventually, but I will never forget how openly oppressive their presence was at what was meant to be a march for liberation.

A quick favour. I love writing these posts, and I intend to do them for free for as long as I can. If you enjoyed reading this, forward it to a friend (or three) who you think might like it too. It helps massively, because validation from strangers is truly the only thing that makes the horrors bearable for me.